by Dan Sullivan

by Dan SullivanThe attacks on Medicaid expansion have begun and will intensify as the General Assembly session gets underway. We should wait, they argue, until Medicaid is reformed. By that argument, we should close down healthcare totally. It is service delivery that is broken and demands reform, not the bill payers.

Somehow Medicaid recipients are to blame for doctors who bill

for procedures never performed, pharmaceutical companies that raise

prescription prices because they know insurance will cover “negotiated” costs,

insurance companies that create twisted access structures that are a barrier to

treatment and that maximize profits, companies that price medical record software to

gouge tax credits, and accountants and clerks who embezzle revenues. Yes, your

tired, your poor, your huddled Virginians yearning, no desperate, for care are

relegated to emergency rooms one way or another where a single visit might be

billed at a rate greater than the annual cost of a full year of Medicaid

preventative care. And all of this the recipients’ fault, so cut them off.

Oh, and we are to suppose none of this ever happens in the

private sector to for-profit health insurance companies. Get a grip, Republicans,

you used to be the party of business but you’ve become the party of busybodies.

Sunday we were treated to a litany of situated arguments about why

Medicaid should not be expanded in a

piece designed to play well with the “f&#@ you, I’ve got mine” crowd.

Seven reasons without real reason. Keep in mind, there is not a footnote or

reference in the column.

First, it seems it took a team of renowned

economists to discover that Medicaid enrollees place a low value on the program.

We are not told who, what, why or where those recipients were polled. You see,

in Virginia the vast majority of Medicaid recipients are under 19. Children are

important, but we shouldn’t be guided by their healthcare opinions. Somehow

this low valuation is twisted so that it rises from the fact that Medicaid

spending benefits large institutions, like hospitals, nursing homes, and

insurance companies, most. Well, yes, you can be certain that providers do gain

a substantial benefit from having their costs covered and not being expected to

run charities to support their going concerns. But how you measure that “most”

judgment can influence the outcome and it certainly seems that asking consumers

about service from a program that requires constant intrusive management will

affect attitudes and responses. So does resentment that other paths to access

are unavailable. This kind of survey would be an opportunity for the frustrated

to vent since no one else, including the legislators who deny them access, has

asked.

First, it seems it took a team of renowned

economists to discover that Medicaid enrollees place a low value on the program.

We are not told who, what, why or where those recipients were polled. You see,

in Virginia the vast majority of Medicaid recipients are under 19. Children are

important, but we shouldn’t be guided by their healthcare opinions. Somehow

this low valuation is twisted so that it rises from the fact that Medicaid

spending benefits large institutions, like hospitals, nursing homes, and

insurance companies, most. Well, yes, you can be certain that providers do gain

a substantial benefit from having their costs covered and not being expected to

run charities to support their going concerns. But how you measure that “most”

judgment can influence the outcome and it certainly seems that asking consumers

about service from a program that requires constant intrusive management will

affect attitudes and responses. So does resentment that other paths to access

are unavailable. This kind of survey would be an opportunity for the frustrated

to vent since no one else, including the legislators who deny them access, has

asked.

There is another thing that isn’t addressed, maybe because

these renowned economists don’t spend time in the field. This is something you hear

consistently from people who are former clients of “free” or sliding scale

clinics but newly able to obtain health insurance under the Affordable Care

Act. They are accustomed to the kind of care and dignity afforded patients at

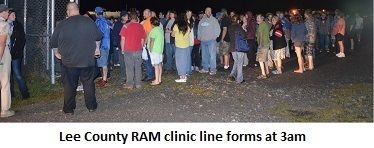

these facilities and at clinics like those provided by Remote Area Medical. They mistake the often disinterested and sometimes rude

treatment all of us who have always had insurance have experienced from

reception personnel in medical offices as being looked down upon because of the

insurance card they present. This is particularly characteristic of the “Doc in

a Box” medical facilities, not only at the front desk but throughout the

treatment and final farewell at the payment window. If they are going to get treated

poorly in those offices, they’ll just use their cards at the emergency room

where they don’t need an appointment and the staff is too busy to hate on them.

The second point presented is that the healthcare outcomes for

Medicaid patients is worse than those of “similar” patients without Medicaid.

Are you serious? Without knowing exactly what is meant by “similar” it is easy

to guess that this is cherry picked data; apples and oranges or peas and

carrots for those who made it all the way through Econ 101 or less but whose

predisposition is reinforced by such inexact comparisons. For Virginia almost

everyone between 19 and 65 who is not pregnant and meets Medicaid income limits

isn’t on Medicaid. This comparison is absolutely meaningless for Virginia.

Though, it would not be surprising that low payments to providers would affect

“service.”

Then there is the argument that Medicaid recipients receive a

disproportionate amount of non-emergency care in emergency rooms. Supposedly recent

data suggests that the Medicaid expansion has made this problem worse, not

better. Again, shape your data to your purpose. If low payments affect service

then maybe this is self-fulfilling. Poor service from non-emergency providers

may drive Medicaid recipients to emergency rooms where at least they know they

have to be seen. Come on now.

The fourth reason presented makes one wonder if the researcher

has spent time in the market at all. “Medicaid expansions tend to cause people

to replace their (often superior) and privately financed coverage with

Medicaid.” The argument all along has been that Medicaid is inferior. Now

somehow private sector insurance is only “often” superior. And one may only

imagine that the meaning of “superior” can be misleading. Does it include

affordability? Who knows? Doubtful the researcher does. But understand this:

under the Affordable Care Act, one may not arbitrarily drop coverage in the

private sector and find themselves eligible for a government insurance program

or subsidized insurance. That is not the way it works. But that is inconvenient

for the argument’s sake.

You have to love the fifth reason presented:

”Medicaid spending is already rapidly increasing, threatening other state priorities. Over the past 25 years, Virginia’s Medicaid spending, adjusted for population growth and inflation, more than tripled. Between 1989 and 2014, Medicaid more than doubled as a percentage of total state spending, while the share of spending going to elementary and secondary education, higher education, and transportation has all dropped.” – from the RTD opinion piece

So, we are to compare today’s costs to the days when many, many

more children went without healthcare coverage and access. We are to blame the

General Assembly’s good decision to previously expand Medicaid through programs

like FAMIS for the General Assembly’s bad decisions to cut spending on

education during the economic downturn when the General Assembly was protecting

Governor McDonnell’s smokescreen of fiscal responsibility that included defunding

the Virginia Retirement System to balance the budget. And, of course it is

Medicaid’s fault that median income took a huge dive at the end of the Bush

administration; a recovery from which is almost complete due to the Obama

administration’s diligent stewardship. No, that change in relative spending was

the choice of a Republican dominated General Assembly poised now to continue

another monumental mistake having already passed on what is approaching $3 billion of our own tax money that could have expanded Medicaid, stimulated the Virginia economy, and lowered

long term healthcare costs in Virginia.

Next, he argues that states adopting the ACA Medicaid expansion

have experienced much larger enrollment and spending increases than expected. “More

than twice as many people enrolled in Kentucky as expected, more than doubling

the expansion’s cost to the state. Twice as many as expected also enrolled in

Washington, and nearly three times as many as expected enrolled in California.

In Michigan, costs are 50 percent higher than anticipated, and Ohio’s costs are

more than twice what was anticipated.”

No. Not doubling the cost to the states. Again, that is federal

money not state money. And if the need has been that great, that alone is an

indictment of the economy that a certain Republican administration left

for others to right. This is part of the cost of bad economic policy and

ignores the greater fact:

The insurance pool is the insurance pool. It does not

change with insurance coverage. Someone is going to pay for the care,

the much more expensive emergency room care, of those without health insurance.

That someone would be everyone who has health insurance that will pay the costs

of uninsured patients that is passed through to and spread among all paying

patients, insured or not.

The final argument is even more ridiculous than

all others. It cries that some Virginians will lose their subsidized coverage

in the Federally Facilitated Marketplace (FFM) if Medicaid is expanded. Okay,

let’s get this straight. There is a window opportunity for those with household

incomes between 100% and 138% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) that Medicaid

expansion denial opens to Virginians. So we should not expand Medicaid coverage

to all below 138% FPL because Obamacare already covers some small sliver of

that population through state legislative omission. We should defend those who

are eligible for coverage under Obamacare against becoming eligible for coverage

under Obamacare at what will almost universally be less expensive than coverage

through the FFM.

The final argument is even more ridiculous than

all others. It cries that some Virginians will lose their subsidized coverage

in the Federally Facilitated Marketplace (FFM) if Medicaid is expanded. Okay,

let’s get this straight. There is a window opportunity for those with household

incomes between 100% and 138% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) that Medicaid

expansion denial opens to Virginians. So we should not expand Medicaid coverage

to all below 138% FPL because Obamacare already covers some small sliver of

that population through state legislative omission. We should defend those who

are eligible for coverage under Obamacare against becoming eligible for coverage

under Obamacare at what will almost universally be less expensive than coverage

through the FFM.

There is an attempt to justify all of this by arguing that this

is a fiscal issue. No kidding. With this one would have to agree but not with

the premise. There is no acknowledgement of what has already been pointed out:

Virginians and all Americans have some sort of access to healthcare whether

covered by insurance or not. The little game we are being asked to play here is

to pretend that denying access to preventative care will somehow lower health

care costs in the long run and that it is fine for those with coverage to pay

for those without coverage as long as we do it in the most expensive manner.

Nevertheless, the opponents of improving health care delivery in

the General Assembly will be trotting out these arguments soon enough. What

will be interesting to hear is any proposal for a Republican Alternative

Medicaid (RAM) program. That has a nice ring to it. It can be modeled on Remote

Area Medical. In fact, it would not be surprising, since gubernatorial

candidate Rob Wittman dropped by the November Warsaw Clinic for a looksee, that

he might propose combining the two (although he hasn’t posted anything on his

website about the visit or the clinic). Maybe a public-private partnership

where the state matches the dollar value generosity of private donors and

volunteers would meet muster. At the Remote Area Medical clinics the patients

don’t complain about the service; only that it doesn’t come round more often.

That would salve the argument that seems to be the underlying

theme of those opposed to expansion and the one cited first among their

arguments: recipients aren’t grateful enough for us to be bothered.

Translation: they don’t vote for us anyway, so screw them.